Recently, Danver wrote about a brilliant implementation of the Hangman game in just three lines of Python. But the shortened code might be hard to understand. In this post we will rewrite his code in a more idiomatic Python 3 style.

Spoiler Alert: If you prefer a fun exercise, try doing it yourself first and then compare with my version.

Danver’s implementation cleverly uses the system dictionary (pre-installed in Linux and Mac, but we’ll see how it can work in Windows too) for picking a random word. It also displays a neat ASCII-art hangman at every step. Except for a few minor improvements, I have tried to retain the essence of Danver’s original in my rewrite below.

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""A simple text-based game of hangman

A re-implementation of Hangman 3-liner in more idiomatic Python 3

Original: http://danverbraganza.com/writings/hangman-in-3-lines-of-python

Requirements:

A dictionary file at /usr/share/dict/words

Usage:

$ python hangman.py

Released under the MIT License. (Re)written by Arun Ravindran http://arunrocks.com

"""

import random

DICT = '/usr/share/dict/words'

chosen_word = random.choice(open(DICT).readlines()).upper().strip()

guesses = set()

scaffold = """

|======

| |

| {3} {0} {5}

| {2}{1}{4}

| {6} {7}

| {8} {9}

|

"""

man = list('OT-\\-//\\||')

guesses_left = len(man)

while not guesses.issuperset(chosen_word) and guesses_left:

print("{} ({} guesses left)".format(','.join(sorted(guesses)), guesses_left))

print(scaffold.format(*(man[:-guesses_left] + [' '] * guesses_left)))

print(' '.join(letter if letter in guesses else '_' for letter in chosen_word))

guesses.update(c.upper() for c in input() if str.isalpha(c))

guesses_left = max(len(man) - len(guesses - set(chosen_word)), 0)

if guesses_left > 0:

print("You win!")

else:

print("You lose!\n{}\nHANGED!".format(scaffold.format(*man)))

print("Word was", chosen_word)

You can view or download the gist on Github as well.

HO_ IT _ORKS

The code makes excellent use of Python’s built-in set data structure and string format function.

Right after a boring module docstring and the import statement, we initialize the following variables:

- DICT: Path to a dictionary file

- chosen_word: Randomly picked line (aka. a word) from DICT

- guesses: Set of letters guessed by the user, so far

- scaffold: Hangman drawn in ASCII art as a format string

- man: Missing ASCII characters for

scaffold - guesses_left: Remaining letter guesses

The while loop, whose exit condition will be explained soon, is our main game loop. The first print function reminds you the guesses you have entered so far (in alphabetic order) and the number of guesses left. The next print function shows the ASCII hangman with enough missing parts from man based on the number of wrong guesses.

Finally, the third print function shows the chosen_word by revealing only the characters from your guesses and replacing the rest with underscores. In the following line, we read a character or even several characters from the user, uppercase them, filter out the non-alphabets and update the guesses set, all in a single line:

guesses.update(c.upper() for c in input() if str.isalpha(c))

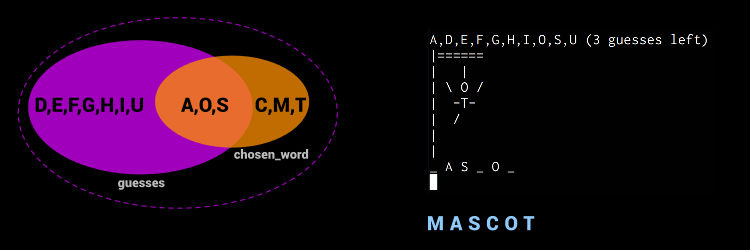

Next, we calculate the number of letters we got wrong. As the diagram below shows, this is the difference of the sets guesses and chosen_words (In the diagram, the letters - C,M,T). We find how many guesses are left by subtracting the set of letters of man from the letters we got wrong. The max function ensures that we don’t go below zero.

Eventually, you could win if your guesses cover all the right letters. In the language of sets, this is when guesses set grows large enough to become a super set of chosen_word set. This is indicated by the dashed purple circle. Hence, the while loop will continue until this happens or we run out of remaining guesses.

Finally, we show a win or lose message based on whether we ran out of guesses. In either case we reveal the initial chosen_word.

IMPRO_EMEN_S

For comparison, here is Danver’s original three-liner:

license, chosen_word, guesses, scaffold, man, guesses_left = 'https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT', ''.join(filter(str.isalpha, __import__('random').choice(open('/usr/share/dict/words').readlines()).upper())), set(), '|======\n| |\n| {3} {0} {5}\n| {2}{1}{4}\n| {6} {7}\n| {8} {9}\n|', list('OT-\\-//\\||'), 10

while not all(letter in guesses for letter in chosen_word) and guesses_left: _, guesses_left = map(guesses.add, filter(str.isalpha, raw_input('%s(%s guesses left)\n%s\n%s:' % (','.join(sorted(guesses)), guesses_left, scaffold.format(*(man[:10-guesses_left] + [' '] * guesses_left)), ' '.join(letter if letter in guesses else '_' for letter in chosen_word))).upper())), max((10 - len(guesses - set(chosen_word))), 0)

print 'You', ['lose!\n' + scaffold.format(*man), 'win!'][bool(guesses_left)], '\nWord was', chosen_word

Got it? Okay, maybe it needs a bit of explanation. Python is a whitespace-aware language designed for maximum readability. So it takes a lot of questionable tricks to write one-liners, some of which I have used myself in my post “Python One-liner Games”. This time we are going in the opposite direction.

Probably, the most visible changes are:

- License: Mentioned in a doc string rather than as a string

- Import: No longer need to use the internal

__import__function - Scaffold: Multi-line string rather than a one-liner

- Print: Changed from a statement to a function, as in Python 3

- Raw_input: Changed to an

inputfunction, as in Python 3 - C-style %s formats: Replaced with

str.formateverywhere

But, there are also some less evident code changes:

- Loop condition: Replaced list comprehension in

whilecondition with a superset check - Negative index: No need of

man[:10-guesses_left], justman[:-guesses_left] - Set update: Replace

map/filterwith aset.updatei.e. from this:

map(guesses.add, filter(str.isalpha, raw_input...

with this:

guesses.update(c.upper() for c in input() if str.isalpha(c))

- Magic numbers: The number 10 is no longer hard-coded and replaced with

len(man)

As you can see, I have preferred set functions over list comprehensions. The choice of set functions like my_set.update over set operators like my_set += was intentional as the former allows any iterable as an argument and not just sets. In most cases, I have used generator expressions for efficiency.

W_Y PYT_ON 3?

I must admit that the actual reason I rewrote the Hangman was because it didn’t work on my Arch Linux box, which runs on Python 3. Over the last few months, I have completely switched over all my projects (and my book) to Python 3. So far I have had no reason to complain.

Apart from the syntactic differences, you will find some solid advantages of using Python 3 versus Python 2:

-

Unicode files: Since the dictionary file path can be changed, I created a test file with a few Malayalam words in separate lines. The Python 2 version just exits with a win message. This is probably because

str.isalphafilters out all the characters. Whereas, in Python 3, everything just works. -

Removes arcane forms: No more

raw_input(who uses the oldinput?) orprintstatements

If you are on Windows, you can download pretty much any of the dictionaries online (even the offensive ones) and change the path in DICT to something like dict.txt. Or, you can create a simple text file with one word on each line. Pro Tip: Hangman is great for learning foreign languages so try creating a Unicode file with some foreign language words.

Before any of the Python 2 fans lash out on me, let me note in the passing that this code will work perfectly on Python 2.7+ if you replace input with raw_input. Cheers!

FI_AL COMME_T

This post is by no means a critique of Danver’s code. In fact, I loved his implementation and totally didn’t waste my weekend playing Hangman (27 wins out of 30 games!!!). It had a lot of fun mapping the problem to sets and making small improvements.

Hope you found some new Python best practices or just an awesome word game to kill time!